There’s No Fun in Funny Games

Austrian filmmaker

Michael Haneke went back to the drawing board in 2007 and redirected an

American version of his previous film Funny

Games shot-by-shot. Known for arising social issues in his work, Haneke

takes a crack at deconstructing violence in a particularly reflexive manner.

Falling under the horror/thriller genre, the conventions are frequently

subverted and criticized throughout the film. Haneke demands his audience to

watch a moving picture of the genre, while analyzing it simultaneously.

Funny

Games is an incontestable battle between

two theatrical genres, the first being Aristotelian tragedy. It implies a

terrible occurrence befalling innocent unsuspecting

individuals. It doesn’t focus on tragic events, but on how they affect the

protagonist(s) and determine their fate. By empathizing with the film's victims,

the viewer is allowed to better understand the consequences of violence. At the

same time, Haneke makes use of Bertold Brecht’s distanciation technique found

in Brechtian Theater, which in turn shatters the cinematic “fourth wall”. Distanciation

is employed in order to interrupt the viewer’s process of identification with a

particular character and allow room for contemplation instead. Here, the audience

feels little or no empathy. Instead, one watches the violence as a distanced

observer, removed from the actions taking place entirely and immersed in the

mindset of “It’s just a movie”. This film is purely about duality. It is

contradictory through and through. We are constantly asked to empathize with

the characters and the next minute we are forcefully detached.

The majority of film-goers want their

entertainment to be a fun – or in this case funny

- thrill ride, completely free from any sort of responsibility. In Funny Games however, the struggle occurs within the viewer rather than the

fictional characters. Haneke makes us pull back and question "What exactly

entertains us?" And even pushes it further..."What is

entertainment?" The director dares to involve his audience in his work, inciting

us to react to extreme situations. We have no choice but to feel the pain of

the physically and psychologically tortured Farber family and then we are

suddenly distanced and asked to reflect upon the events. The film is not meant

to be mere entertainment, but a critique of entertainment in and of itself.

This is the reason behind entertainment and pleasure being the answer to Anna

Farber’s frequently asked question "Why are you doing this?" The

violence being critiqued in Funny Games

is the same that can be found in the thousands of horror/thriller films that are

made for the sole amusement of audiences. Nevertheless, this is clearly not a

motion picture that one watches to obtain leisurely pleasure, but to reflect

and ask "What pleasures me and why?" In result, Haneke’s vision cannot

be pigeonholed as a horror film because it brings much more to the proverbial

table.

Funny

Games also deals with the topic of

complicity. Peter is considered the sidekick. He is present and participates in

all the violent actions towards the Farber family. He however doesn't

personally harm any of them. This makes the audience reassess their role in

society by nonchalantly taking in violence in a practically apathetic manner.

Are we ultimately all "Peters" participating in and accepting

violence? “Why don’t you just kill us”, asks Anna and the perpetrator replies,

“You shouldn’t forget the importance of entertainment.” Although being a clear

protest against violence, this dialogue is directed directly to the viewer. Yes

– it can imply that society these days is gluttonous, never satisfied, and always

wants more to a disturbing level, but these characters are abusing their

victims for our pleasure. In sum, we

the audience is taking part in crime.

The director wishes to

trigger us and urges us to react to violence and its current portrayal in

modern cinema. In accordance with his previous film Benny's Video (1992), Heneke prides himself in making a social

commentary on violence and the way the masses take it in and consume it as if

it were any other generic theme or topic. He chooses to film television sets as

mediators when violence occurs. In Benny's

Video, you are prodded to stare at a film within a film of a murder, while

in Funny Games you are incited to

watch a Nascar race on a blood-drenched TV; all this amid hollers of agony. Haneke

denies the audience’s expectations of ketchup-blood and gore by making almost

all the violence occur off-screen, leaving the viewer with nothing but sounds

of struggle and pain. Hence, what we don't see creates a more powerful effect

on the viewer. We are left with a more gruesome image; the one we concoct in

our minds. With one sense being denied, another's intensity is heightened.

Heneke creates meaning by ultimately NOT giving the audience the desired image.

Another intriguing

instance in the film is once the Nascar "film "(or televised

event)-within-a-film scene is over. We are immediately pulled back at a

distance in a full shot during a long take of Anne Farber struggling; only to

press the television's off button rather than tending to her murdered son.

Here, Heneke decides to strip away all numinous elements of parenthood. We as

viewers are again denied our expectations.

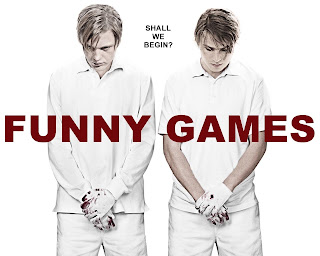

He subverts the

conventions once again in his selection of “the bad guys”. Paul and Peter appear prim and proper and come

off too cordial for comfort. The duo is enrobed in strictly white garments that

traditionally symbolize purity and catharsis. This color is usually associated

with the good. Heneke though decides

to camouflage his culprits by anglicizing them by their names and colors of their

clothes. Also, the offender’s golf gloves can be regarded as symbols of belonging

to the middle-upper class, which is not common for most criminals. The well off

tend to not get their hands dirty, but this emblematic piece of clothing can

also hint towards the “criminal”. The two refuse to take responsibility for

their actions and don’t feel any remorse. A spectator can easily be baffled by

a polite murder, hence Haneke gives a new meaning to the saying “Kill with

kindness”.

On the topic of sound,

Heneke evidently manipulates his audience. The sound and music found in Funny Games is mostly diegetic. During

the opening credits, the Farber family is playing a guessing game of classical

music on their car ride towards their country house. Another example is when

Paul is chasing Georgie Farber in the neighbors’ house and puts on a record.

Other than that, the film is basically composed of room noise to install the

viewer in the action and make them a part of the film living with the characters. The only instance of non-diegetic music

is that of Naked City’s Bonehead. It is out of context

but used as a distanciation method to alert the viewer that this family is

going to have an undesirable upcoming fate. The song is further employed when

Georgie is prepared to shoot Paul with a rifle. We are cued to feel anxious and

pushed to the edge of our seats until we see that the gun is unfortunately not

loaded.

On a cinematographic

note, Funny Games, although being an

American carbon copy of its European version, stays true to form. The film

isn’t a plot weaved together by “shot - counter-shots” and quick cutting.

Haneke utilizes the long take to keep us locked in the moment and appreciate engaged

performances through close ups of facial expressions depicting real human emotion. A striking scene is

that of a golf ball slowly rolling down the hall and into the center of a

mid-shot of the doorframe as the father, George Farber, automatically

associates this image with the return of the white-dressed torturers from the tormented

look in his eyes. This asserts that Haneke doesn’t give you all the answers and

images you want or expect to see. He doesn’t guide the viewer, he trusts his

viewer as a meaning-producer.

All things considered, Haneke

doesn’t desire to please his spectators. He’s not the least bit interested in

giving you the plot on a silver platter, nor patting you on the back in the end

telling you “it’s OK”. His main concern is conveying an idea and producing a

responsible film. He is undoubtedly an auteur because he does this by

subverting the conventions of the genre at hand and creating a cinematic dichotomy

that shakes the viewers and breaks the illusion.

Funny Games allow you to unleash your anger and forget the travails of modern day life.

ReplyDeletefunny games

Funny cat memes Fantastic blog.Much thanks again.

ReplyDelete